Spoiler alert: if you don’t want solutions to project euler problems 31 and 78, stop reading now.

I want to write about these problem, because although they seem similar (and are mathematically similar) they require somewhat different solutions in order to run in a reasonable amount of time. Also, it will give me a chance to explain my thought process a bit.

Problem 31

This problem asks how many different ways you could make 2 GBP with regular British currency (1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, or 200 pence). You might recognize this as being similar to the problem of finding partitions of integers.

How do we approach this problem? First, we notice that there are a lot of choices to make when trying to find a way to build 200 out of our list of values, so a “bottom-up” approach probably won’t work. That is, if we decide to start with a coin value, say 5, and then pick another coin value, say 10, and keep doing this until the sum equals or exceeds 200. Then repeat for every starting value.

If you do it this way, it’s basically impossible to do any sort of dynamic programming. You’ll need to do the same computations over and over again, and there’s not way to avoid this.

A much better solution is to use the tree-like structure natural to this problem and recurse. Here’s what I mean: start with 200, then substract off every possible coin value: .

There’s a catch though! Once you subtract a coin of value , you’re never allowed to substract a coin of value larger than in the same branch of the tree. This is to guarantee uniqueness of the partitions (i.e. so we don’t count both and as different partitions.)

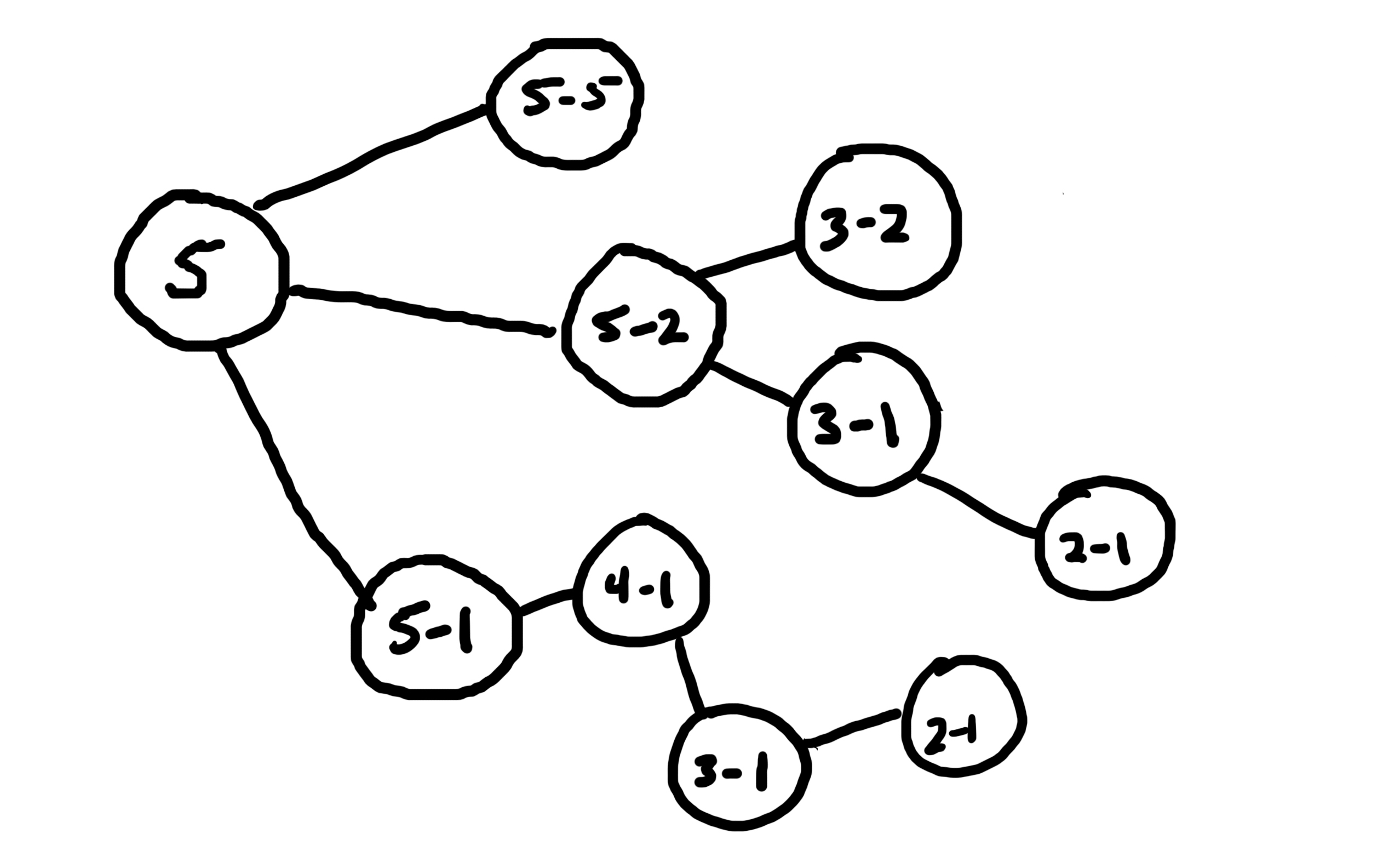

Here’s a sketch (literally) of what’s going on in my head when I think about finding ways to make 5 pence out of other coins.

Notice that each branch of the tree gives a different partition of 5 in terms of the coins 5, 2, and 1:

To get the number of way to make 5 out of these coins, simply add up the number of branches in the tree!

Of course, there is a way to speed this up: we can have the computer keep track of already computed values! But remember, in the above image, even though , the number of branches from each of these nodes differ. This is because we aren’t allowed to subtract coins bigger than 1 off the value of . So, we don’t only need to remember the value of , but also .

Here’s a solution in python:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 | |

Something to think about: what happens if we didn’t have a coin with value 1? How would we need to change this?

Problem 78

After I wrote the function above, I went looking for other problems where I could use it. I found problem 78, which asks to compute the smallest positive integer for which the number of partitions, , is divisible by 1,000,000.

Notice that finding integer paritions is a special case of the above coin-finding problem, such that for any value , the set of coins is {}.

If you want, you can start printing out values for using the above function. You’ll find that gets very large very quickly (hundreds of digits once reaches the thousands). Even with caching, we need something much quicker.

Euler to the rescue!

Luckily, Euler proved the wonderful formula: where and if then . So at least with this formula, the time it takes to compute is linear in .

Unfortunately, this approach only works for partitioning, and we don’t have a similar formula for general coin-finding problems (at least, I don’t think so…).

So, the next step is to write a dynamic algorithm in python that implements this. (Don’t try to run the following code. Trust me. I’ll explain in a bit.)

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 | |

If you’re interested, you can insert a print statement into the loop and watch get big. By the time you hit I think you’ll be looking at 100 digit numbers. You’ll also wonder why you haven’t seen 6 zeroes at the end of any of these numbers yet, and eventually python will try to convert infinity to an integer and throw an error.

There’s one last thing to do, and I’ll admit it took me an embarassingly long time to think of it. We only need to keep track of the last 7 digits of . Because of the way modular arithmetic works, and because Euler’s formula only involves adding and multiplying, instead of keeping in the list “part”, just store % .

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 | |